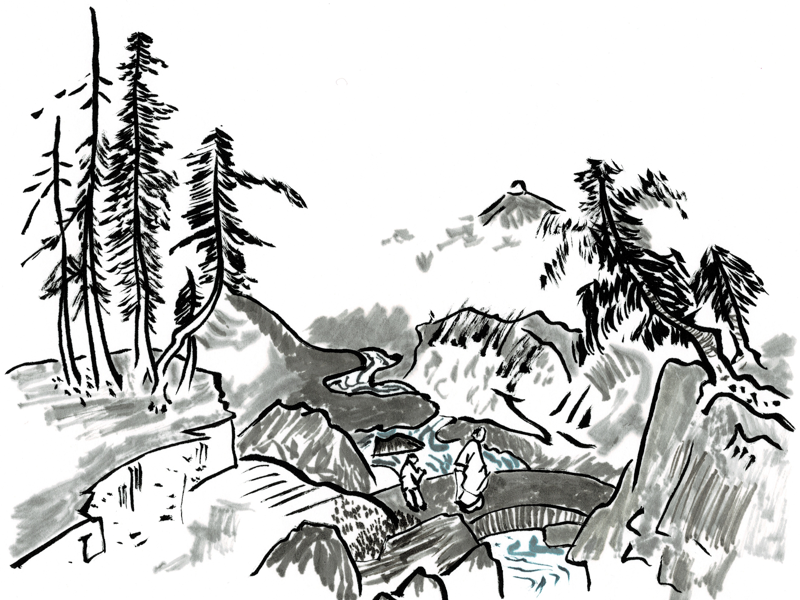

These three scroll blanks are traced from a frame captured from “The Tale of Princess Kaguya” a 2013 animated film Studio Ghibli. This film is beautiful, and has a large number of beautiful images in it.

This modern animated film is based on an anonymous 10th-century folk tale called “Tale of the Bamboo Cutter”. It follows the life of a mysterious baby girl who is found in a shining bamboo stump and raised to be a princess by a poor childless couple.

For almost a decade following its release, this was the most expensive Japanese film ever produced, possibly due to the art style that is based on the Yamato-e style of old Japanese illustrated scrolls (emaki). In 1999, director Takahata published a book called “From a Painting” in which he explored traditional Japanese art and its ties to his animation.

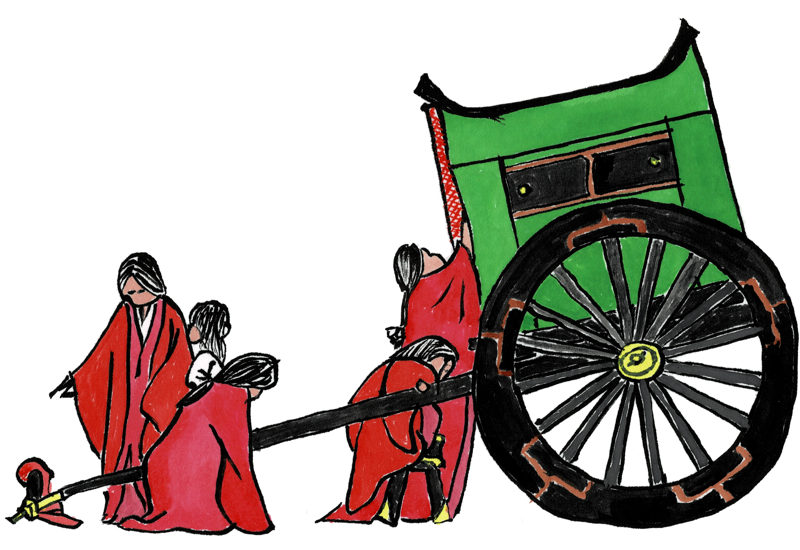

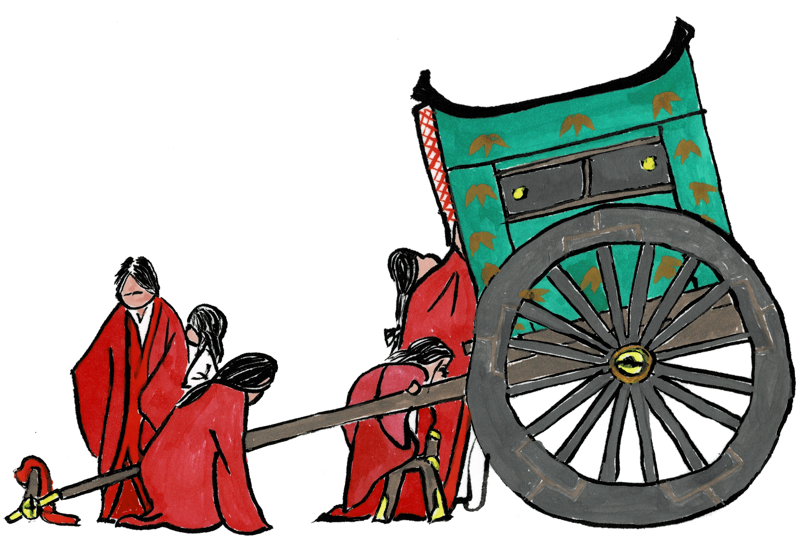

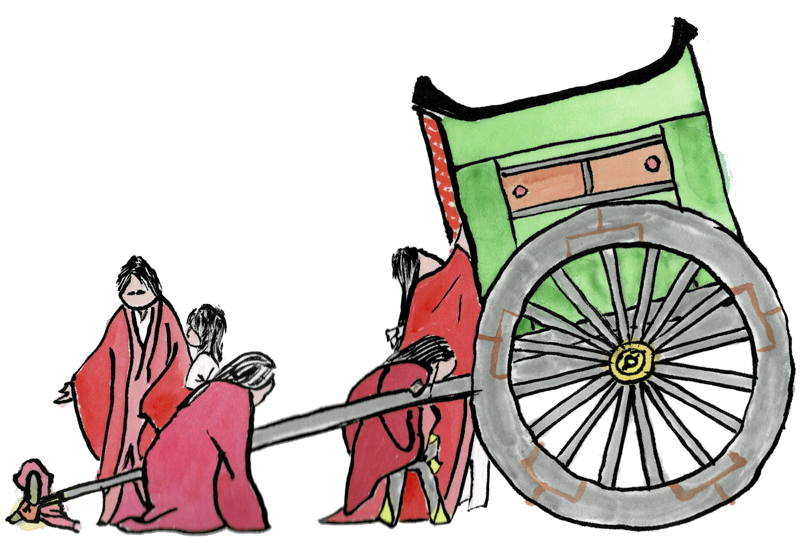

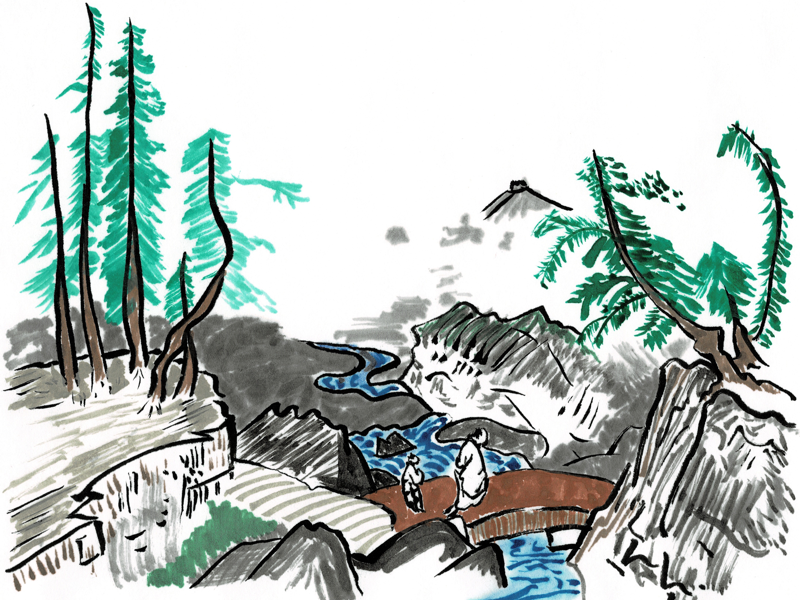

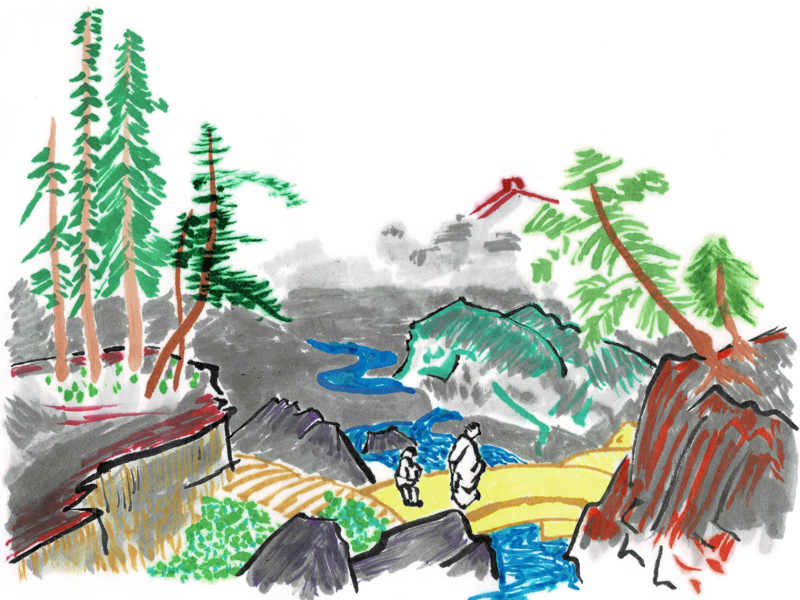

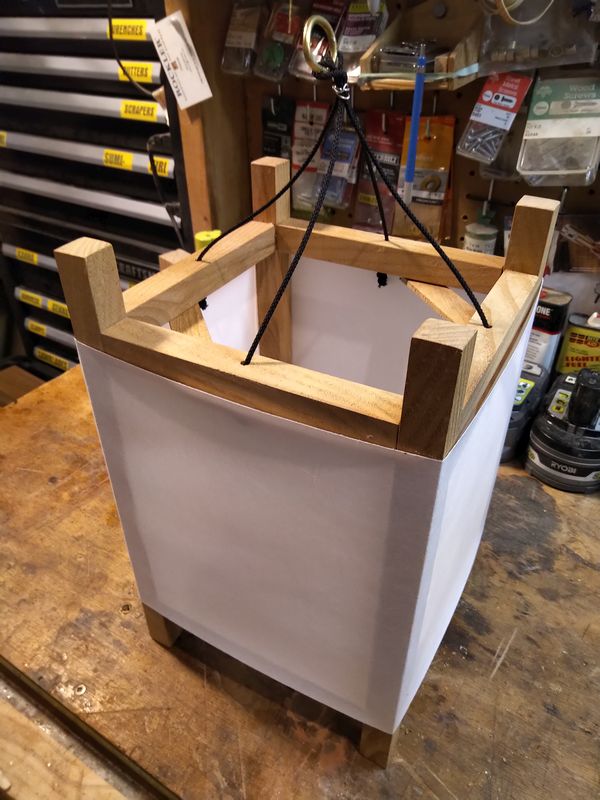

In this image, the devoted maidservants of the Princess ready her cart for travel.

This one, I think I laid the color on a bit heavy. It’s vibrant as heck, but you can’t tell that the maid’s gowns are four different colors.

This one’s a bit lighter, but still too heavy. I tried a different green on the cart, and embellished it with bamboo leaves the way it is in the film, though.

This one is so much lighter, and you can really see the different hues on the robes. I’m starting to get the hang of using really watery mixes of paint to wash color into the paper. The paper is super-absorbent, so you need a light touch to keep from creating blobs of color. Super happy with this one.